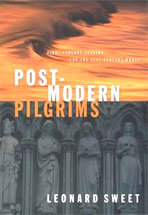

The Purpose of the BookIn the book Postmodern Pilgrims by Leonard Sweet, the author sets out to discuss the nature of the postmodern culture and how the Church should respond. Sweet feels that there has been such a dramatic change in the culture that if the Church does not change the way it does things, it will lose the culture. Sweet quotes Romano Guardini who said, “Today the modern age is essentially over” “The church was on the right track, he argued, but riding the wrong train” (XIII). Sweet believes that the modern period with its strong focus on propositions, and rationality, was a mere stint in time, which is now over, but not without taking a firm hold on the Church. In this book Sweet wants to call the Church to return to what he believes the original Church was intended to be. He argues that if the Church is going to be authentic in its worship and reaching the postmodern culture it’s going to have to make some significant changes, which will be dealt with in detail shortly.

In attempting to lay out his foundation for this book, he makes a few statements regarding it. (1)”Postmodern Pilgrims is an attempt to show the church how to camp in the future in the light of the past” (XVI). (2) Postmodern Pilgrims argues that ministry in the twenty-first century has more in common with the first century than with the modern world that is collapsing all around us” (XVII). (3) Postmodern Pilgrims aims to demodernize the Christian consciousness and reshape its way of life according to a more biblical vision of life that is dawning with the coming of the postmodern era” (XVII). With these in mind, he states that the point of this book is to introduce the EPIC model of “doing church”. Before moving on he makes a clear warning that as Christians we are not to embrace a postmodern worldview, because there are aspects of postmodernism which are in direct contradiction with the truths of Christianity.

PremisesThe book has two significant underlying premises. (1) The first one is that the modern period has ended. The culture has changed significantly. It is no longer concerned with rational thought and logical argumentation. We live in a culture that does not try to figure everything out. Mystery is embraced; reason has been critiqued, and found to be wanting. Terms like foundationalism and rationalism are now suspect. Therefore people are more concerned with the experiential and less concerned with propositional truth, if there even is such a thing. To add clarity to this premise, Sweet is clear to let us know that the focus on propositions were products of modernism and now we are returning to a more Biblical understanding. A more “eastern” understanding is the way the Bible was originally meant to be read. (2) The second main premise that he deals with, is that the Church is stuck in its modern trappings and needs to shaken free of them. If it does not, it will fail, besides it is not what the church was intended to be.

The conclusion of these premises is that the church needs to change the way it does church. The first real problem with the book is that both premises contain serious error, but are never really addressed. The majority of the book is spent trying to tell us why the Church ought to follow the EPIC model by using examples of successful businesses and other postmodern groups that are making an impact. An interesting aspect of this is that the beginning of the book starts out by decrying the crass commercialism that the Church has bought into, and then uses Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and eBay as examples of how the church should change if it wants to be successful. If these are not pure examples of commercialism then what is.

The book starts off with an introduction called “Kiss and Tell” (1). Sweet tells three romantic stories and tries to let us know that we are pushing away the culture when we should be trying to love it. He says that our method of dealing with the culture is to tell it to change and then it will start to love it. He says that we should not do this, instead we should love it and then it may change. The problem with this argument is that he never specifies what aspect of the culture he talking about. If he’s talking about the people in the culture then he is right. Scripture has been telling us to do this since it was written. We are to love others, even our enemies. But if he is talking about the postmodern worldview that teaches the there is no real truth, and ethics are feelings, then he is wrong because we cannot, nor should we love it. Since context is talking about the postmodern worldview it is never made clear what he means exactly.

After about 20 pages with headings like “The Holy Kiss” (11) and “Two Great Kisses”(9) and quoting all kinds of music groups from Hootie and the Blowfish to Sixpence Non the Richer, he has somehow made his case that the church needs to change the way it “does church.” The only really significant analogy as to why the church needs to change is because of the way that Who Wants to be a Millionaire has become successful.

E(xperiential)-P-I-CThe first way that Sweet believes that the church should change is that it needs to become more experiential and less propositional in its liturgy. One of his clearest examples of what this means is explained in a metaphor of two signs with arrows. “The right arrow says, ‘this way to heaven’ the left arrow says, ‘this way to a discussion about heaven.’ The modernist took the fork to the discussion. Guess which fork the postmodernist took” (31)? Sweet here is trying to say that modernists in the church worship the propositions about God while the postmodernist actually have an experience with God himself. There are clearly some who don’t know God but love theology, but there is a major problem with this idea, because it is never explained what is meant by experience. The best that can be derived from the book is that it is some sort of emotional or spiritual experiences. Some how the postmodernist is actually in heaven while the modernist is discussing it. But in reality neither is in heaven. In fact, a counter example could be made using the two arrow signs. The sign pointing to the right says “this way to heaven,” the sign pointing to the left says “this way to feelings of heaven.” The modernist takes the sign to the right. Guess which one the postmodernist took?

One major problem that seems to get to the root of the issue, is that Sweet uses the following quote by Kant. “There is no doubt that all our knowledge begins with experience” (32). Two major points about this is, (1) it is doubtful that Sweet understands what this is talking about and uses it out of context, (2) or worse he does know what this means and uses it anyway. Kant was an empiricist and believed that you could not know anything that you could not experience with your five senses. Kant then taught that if there is a god you could not know it because you could not sense him.

Sweet also quotes a BMW ad that says, “Engineering. Science. Technology. All worthless unless they make you feel something” (35). The be all and end all for the postmodernist is the feeling you get from the experience. They seem to think this is the truth because they can sense it. This also has many flaws because sometimes our feelings are wrong. The Mormon has the burning in the bosom, the Buddhist has his peace, but neither is true. Not to mention it is never mentioned what actually causes the experience. As Christians, emotions and experiences are important, but only if they brought on by truth, which is not a feeling, but that which corresponds with reality.

E-P(articipatory)-I-CThe next point Sweet addresses is that the culture we live in is a participatory culture. People want options and don’t want to be controlled. They like to be the ones making the decisions which may be true, but he goes on to say, the “’We preach it/You hear it’ is over. Every congregation must become a participant-observer congregation” (72). But hasn’t the church always been doing this? We come together to worship. We sing songs, hymns, and spiritual songs. We study the Word of God as it is preached and we participate in the sacraments. Sweet does bring to mind the importance of small groups where a person can be involved and known personally. It is easy to get lost in a large commercial driven church and not have any participation, but it seems that Sweet sees this as the norm when the truth is that most churches are small churches of about 300 members who have smaller classes and time together. Regardless of the size, there will always be people who will not get involved because they have no interest, and if they were given some say as to the way things should be done, their ideas would have nothing to do with church.

E-P-I(mage-Driven)-C

The next change Sweet believes the Church should make is to be more image driven. His argument is that we should move from a word-based system to a more image-driven system. People today are more moved by images than they are by words. Our MTV generation, with its quick images and news clips say more than words. He then spends several pages writing on the failure of propositional truth and goes on to talk about the importance of metaphors. This was probably the most unclear of the chapters. Why we would want to stop using words and starts using metaphors, which are “word pictures,” doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense.

This Chapter actually contains some serious dangers, because it begins to expose some of the underlying philosophies that he seems to hold to. He says, “Propositions are lost on postmodern ears” (86). Beside the fact that it is self-refuting because he says it with a proposition in a book he has written full of propositions, the statement is simply not true. Everywhere you turn people are telling you what they believe. The conservatives, the liberals, the feminists, and even postmodern philosophers all use them. But what Sweet is getting at is actually more dangerous than he lets on. At one point he actually says that creeds and statements of faith are actually a modern phenomenon, but the Apostles, Athanasius, and Nicene creeds are anything but modern. Doctrine goes back to Jesus himself who the people where astonished with because they had never heard such doctrine (Matt. 7:28). Beside the fact that metaphors are actually propositions because they communicate something that is either true or false, the Word is to be preached. Faith comes by hearing and hearing by the Word of God.

Another problem with this idea is that the Church does and has always used images to teach the Word. That is what the sacraments are all about. The bread and the wine represent the body and blood of Christ. Baptism shows the death burial and resurrection of Christ, and how we have died to our old self and raised to our new man. Images are an important aspect of our worship and will always be.

E-P-I-C(onnected)The final point that Sweet makes is that in a postmodern culture, community is vitally important. He goes on to make some important insights to the fact that we are to love one another and that we need each other. He also spends some time speaking about how we are all connected. Some of which sound something like John Donne’s devotion “For Whom the Bell Tolls”, which is true, but he goes even further and begins to sound more and more existential. Even in this chapter he decries propositions and rules, and lifts relationship to new levels. At one point he goes on to say, “They’re [postmoderns] convinced the world needs less of religion, not more. They want no part of obedience to sets of propositions and rules required by some ‘officialdom’ somewhere. Postmoderns want participation in a deeply personal but at the same time communal experience of the divine and the transformation of life that issues from that identification with God” (112). This is nonsensical because how do you have a community with which you identify, if that community has no rules or propositions that it sets it apart. Even if that is the group you identify with, you at least have one self-contradictory rule, that there are no rules.

Relationship is important to Christianity. We have relationships with God, with our fellow Christians and even non-Christians. But what Sweet is talking about here is harkening back to Kierkegaard, who used to argue that sin is not breaking a rule it’s betraying a relationship. Though this is true, that sin is betraying a relationship, if you have no rules it is impossible to betray that relationship.

Sweet then speaks of love as the highest law, which it is, but he speaks of it as trumping all other laws when in fact it lives in perfect harmony with them. If all other rules are gone then love in turned into a warm feeling, because without laws, rules, and propositions how would we ever know how to express our love. Love is looking out for the other persons best interest even if it means denying our own. Without laws, we would never know if our loving a person is helping or hurting them. To see a homosexual couple and say, “I love you and I just want you to be happy,” this is not loving them, because you are actually helping them continue in a manner that will bring the judgment of God upon them. We are to lovingly help them out of that relationship. God’s moral law is an expression of His love. Whenever we have something that we call “love” that trumps those laws, we’ve deceived ourselves.

Entroduction

Sweet closes the book with what he calls the entroduction. Here he goes into the theoretical background, and his true colors are shown. His epistemology comes out as he says things like, “The other [postmodern] way (more biblical, more Eastern) of ‘knowing” is really a way of ‘unknowing’: to be ‘empty’ of oneself and to let the flower reveal itself as it is” (145). In other words propositions are constructs. He goes on to say that we are bound to our cultural constructions. “Divine revelation has occurred. There are universal moral truths. Yet knowledge about these truths is socially constructed” (146). He quotes an old Jewish proverb that says, “We do not see things as they are but as we are” (148). Sweet seems to hold to the idea that we can’t really know, because it is we ourselves who are bound to our created truths, as we understand. “Observation itself is impossible without some interpretation, that is understanding” (154). Then to keep all the orthodox readers happy he closes with this line, “in a world of Cheshire-cat absolutes, one absolute remains absolute. That absolute is Jesus: the Way, the Truth, and the Life” (155). But how can this be, he has just argued for the last 20 pages that we cannot know without our constructs and interpretation. How can Jesus be an absolute when we know him through our constructs and interpretations?

Method of ArgumentationSweet’s method of argumentation is a hard one to pin down. Like any good postmodern work, logical syllogism are not encouraged. If I where to pick one method of argumentation that he uses to try and convince his reader of his points, it would be argument by analogy. Sweet uses stories and metaphors, hundreds of them, to make his point. Since I don’t believe there is a method of argumentation call argument by metaphor I will stick with argument by analogy. The problem is that the majority of the analogies are neither quantitatively nor qualitatively viable.

Evidence Adduced in favor of the ArgumentsThe evidences he uses to make the majority of his points are the successes of many businesses that are using postmodern methods to create thriving businesses. He does try to use scripture, but the majority is out of context when it is used. He also uses quotes from people like Kant and other philosophers who agree with him, but this is not really evidence.

Postmodern Pilgrims has many problems. Sweet seems to have embraced many of the tenants of the worldview that contradict Christianity, like truth is unknowable, and it is not inherently propositional. The problem with this claim is that if it is true, then the Bible is not of much use to us since it is filled with propositions that we will then construct based on our social conditioning. If God was trying to tell us something, He should have found a better way.

You can’t always take an author by what they say they believe, you have to go deeper into what they are really arguing for. Sweet says that he defends traditional Christianity and that Christ is an absolute, but he spend the rest of the book arguing contrary to the traditional understanding of those statements. By doing so he shows us that he means something completely different when he says traditional Christianity.

Did the Author Accomplish His Goal-Strengths and Weaknesses?The strengths and weaknesses were discussed throughout the explanation of Sweet’s arguments, and since every main section had serious flaws, it seems that the book does not accomplish its goal. Only if someone has already bought into postmodernism, will this book seem convincing, but even then I’m not sure how they would know since they can only know the propositions that he wrote through their social constructions.

The Most Valuable Points Learned from This BookBesides a better understanding of the emergent church movement, I was reminded of the importance of several aspects of Church worship. The experiential nature of Worship is important. The Church should not downplay the emotional and spiritual aspect of worship, but that experience must be truth driven. For instance, when the church sings a hymn like “A Mighty Fortress is Our God” and is moved emotionally as we think about the greatness of our God, and that we do have “the right man on our side, the man of God’s own choosing.” It is truly moved spiritually, but the truth of that song is not made true because the church is moved. It’s true whether or not it’s moved. Experience is important, like Spurgeon said in The Soul Winner, if you want people to feel your sermons you must feel them too. But we must not get this backwards as some in the church have done, because many try to set up emotional experiences in hopes that we will find truth, when in fact we must have truth and respond to it.

I am also reminded of the importance of participation in worship. Not to mention the importance of the images that God has given us in His divine ordinances, and the connectedness that is needed in the Church. I’m also reminded of the trouble we can get into if we raise these things above the truth of God’s special revelation. These must be conformed to the truth, we are not to conform the truth to these things.

Finally this book did remind me that, as the Church, we are to reach out to our culture. The Church is not just to stay in our pews and try to get them to come to us; we are to go into the highways and byways to reach them. The better we understand where they are coming from the better we will be able to go to them and walk them back to the truth, but we must never forget the culture does not alter the truth of God’s special revelation, God truth alters the culture.

-Doug Eaton-